Applying musictherapy to human health, an experience from Africa

Member of the World Federation of Music Therapy, Nsamu Moonga is a young psychotherapist and musictherapist living and working in Boksburg, South Africa.

His perspective on music therapy derives from a decolonized and autochthonous view of community and individual healing practices. His family and traditional relationship with music influences the way he perceives therapy and the work he does with his patients.

The reconnection with our primordial relationship with sounds and voices can be an important tool for various mental and social healing paths, and a way for re-learning to intensely listen to each other and to the world: Nsamu Moonga is a direct witness of this possibility.

He has reminded us of the ancient power of arts with respect to human mental health and wellbeing.

How would you define music therapy practice?

Officially, we define music therapy as the clinical use of music by a trained therapist within a therapeutic relationship, to help clients meet their musical and more-then-musical goals. These goals can be physiological, psychological, emotional and spiritual. I am interested in using music to help clients reach their psychological goals.

I cannot tell you what a typical music therapy activity looks like, as there are many ways music therapists work. I can speak about how the therapeutic music relationship develops through uptake, assessment, development, termination and evaluation. Throughout the process, the therapists collaborate with the client to identify what works and what does not work. Sensitive attention is the hallmark of the therapeutic relationship.

What is music therapy for you?

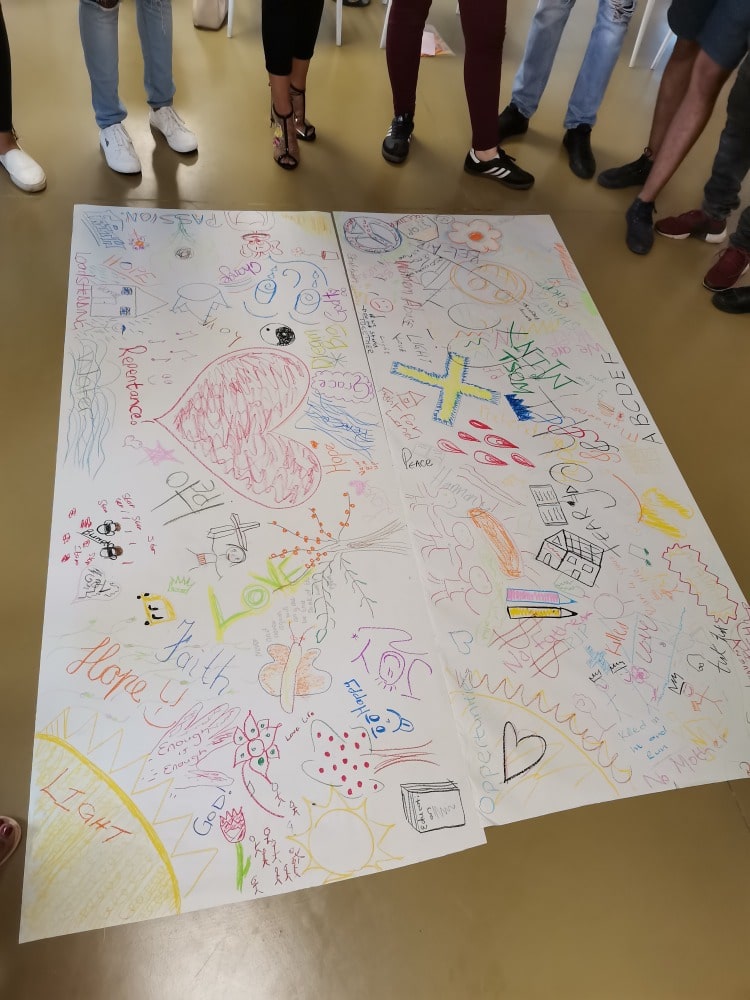

I’d like to talk about another aspect of music therapy. As I have already said, I live in Africa. Africa is a continent where music, musical theatre and musical healing rituals are ubiquitous. As a child, I witnessed and took part in musical healing rituals that lasted days. The community would gather to support the healing path of sick people. I hesitate to call these rituals ‘music therapies’ because I won’t conflict with the legal and official definitions of such registered and formalised practice. In my experience and research, I have come to understand that both practitioners of musical healing rituals and ritual users – such as communities – testify how musical traditions alleviate their pain, strife and affliction. I like to think that music therapy as we perceive it, it is derived from such primordial musical healing rituals.

How did you become interested in music therapy, and why?

As I told you, I grew up witnessing and participating in musical healing theatre. In my neighbourhood, we had ritual healers. They played drums, guitars, marimbas, and various instruments on the nights healing ceremonies were performed. I was only a novice with respect to music and healing. That, coupled with my mother’s influence with singing, turned me into a singer at a young age. We sang around my mother’s teapot most evenings. I grew up thinking that every person could sing until I met a person who could not sing. Later in my life, however, I experienced music in the context of healing when I worked with children and youth at risk. I worked as a volunteer in a community where we used music to sensitise communities and give young people a voice to advocate for their rights. That was pivotal to my direction. I knew then that I wanted to do something in music. I did not know what shape or form it would take until I went to a formal music school. I began to wonder about how music worked in healing settings. I proceeded to do a study of the role of music in traditional healing practice. That study was my pursuing of my curiosity. Alongside music studies, I trained as a counselling psychologist and worked in a clinic for HIV and AIDS. I followed those music studies with further studies in psychological counselling. Then came a time when I wanted to bring my two passions together. I discovered music therapy. I often think that music psychotherapy had been stalking me for most of my life. Music therapy chose me more than I decided.

Where do you work as a music therapist?

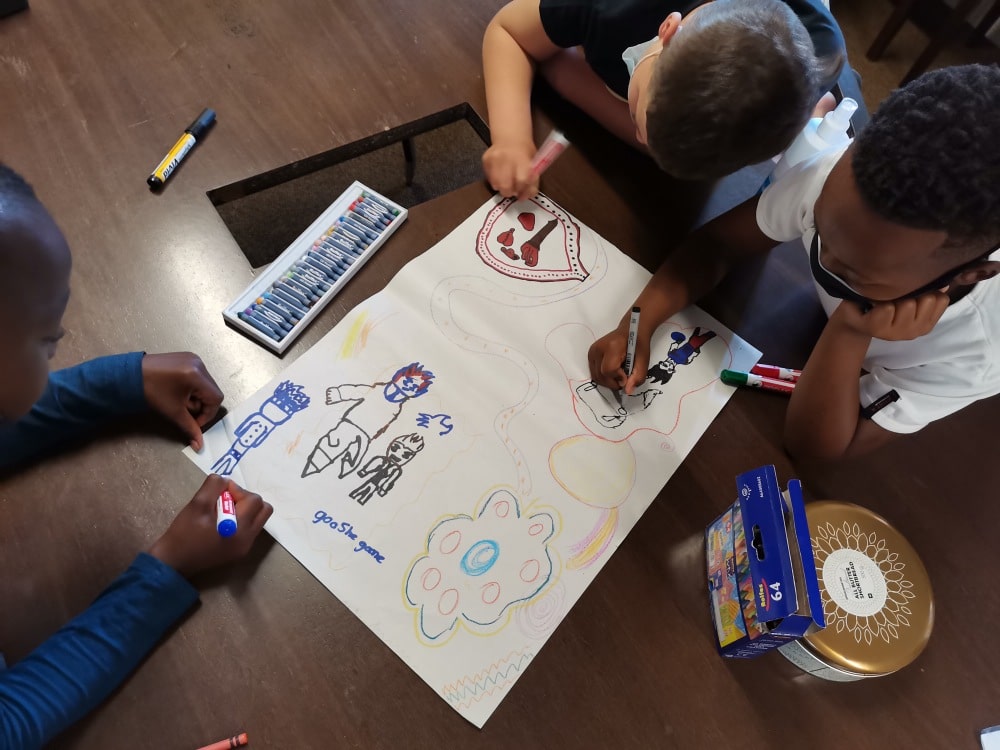

I work in a multiple settings as a music therapist. Music therapy can be employed in multiple sectors, including psychiatric hospitals, schools, public hospitals, special education, trauma units and community building. There is no end to the scope of music therapy. Music therapists work where they feel most comfortable. At present, I work in child and adolescent development setting. I work with young people at risk and young people who have either suffered sexual, emotional or physical abuse or abused others. I am also working in schools to provide preventative psychological and emotional support. In schools, I work to support their staff too.

I work with people in private practice through difficult life transitions such as grief, arrested development, addictions and dependencies, and general personal development needs. I have worked in a paediatric oncology ward, in an acute psychosis ward, substance dependency rehabilitation clinic, children with autism spectrum and older people with dementia in an aged care facility.

In which Music Therapy School did you train?

I trained at the University of Pretoria in South Africa under Drs Carol Lotter and Andeline Dos Santos.

Which are your experiences as a music therapist?

I think of myself as a vocational music therapist. I feel right about being a music therapist. I came to the profession later in my life, which is an advantage to me. All the detours and sidetracks I took earlier seem worth it now. I have come to meet beautiful people in the arts therapies community. I think I am growing well as a music therapist in the world community too. Quite apart from music therapy, it is the making of society that thrills me.

Working with people in clinical settings and community settings is meaningful to me. I like the idea of sensitively attending to a client. I enjoy journeying with other people. By enjoying, I am not suggesting that it is easy. Therapy is hard work for both the therapist and the patient. I think something in the therapeutic partnership also offers me needs I seek to be met in my life. The symbiotic relationship, debatably, is enriching.

Can you tell us how a music therapy session takes place?

What a difficult question to answer, for the reasons that each session is unique. There is no way of working in a predetermined manner with clients as they each have theirs stories and needs. I work within a patient-led paradigm. In most cases, I work with what the client brings to the therapy room. I cannot predetermine how the patient will arrive. Anyway, the session often is based on the typical psychotherapy meeting: from uptake, right through to termination and evaluation. Concerning the music therapy sessions, the best I can describe is when the patient is a child that I might invite to musical improvisation. I can ask them to play a simple rhythmic pattern or melody after me. They can repeat the same way until we decide to vary the rhythm by either extending it or changing the tempo or volume. The session can be a combination of musical offerings to develop the patient and the therapist’s relationship. I think the meeting of people in the music and the space between, is special.

Is it hard to bring art to the psychological therapy’s field?

The musical arts have enhanced my work in psychotherapy, and so, I do not find it hard to incorporate the arts in psychotherapy. They have offered me another window into people’s souls. Because arts are non-invasive, people tend to get over the initial awkwardness of therapy sooner than just talking. Arts are accessible to most people. I think music, in particular, reduces the therapist’s desire to interpret the client as a person. The responses are to the music, the modality as opposed to the promptings of the therapist. Working with the arts frees me to be present for the client to enhance their reflexivity, provided they can articulate their experiences in words.

How do healthcare institutions respond to the practice of music therapy?

In South Africa, music therapy is a registered and licensed practice with the Health Professions Council of South Africa (HPCSA). This suggests, theoretically, that music therapy is welcome in health institutions. Challenges are patterning to the lack of public sector jobs and the institutions managers’ preferences. We are making progress in advocating for music therapy in the country. We are also working on expanding the conversations to other countries of the continent. I only know of Ghana, as the country where music therapy is a licensed profession.

How do your patients “react” to music therapy?

I find it challenging to make a generalised statement about the patients’ responses to music, apart from how the music facilitates the development of the therapeutic relationships, and resultantly the change that is observable in the client’s demeanour. I have had an experience where the mood of the patient has dramatically shifted after a drumming improvisation. Another one exclaimed: “I have not felt like this in a long time”, at the end of the improvisation.

Patients respond differently to music, whether it is improvised music or deliberately composed music or pre-recorded. I think the client specificity in art therapy make it accessible. While a therapist can rely on techniques, what is vital in our case is the open attentiveness to the client’s need and letting the music do the work.

How many African music therapists do you know? Do you work together?

We are in the process of drawing a dataset for music therapists on the continent. There is a lack of data regarding practitioners. I am aware that one music therapist is practising in Chad. There is one professional music therapist in Ghana, about four in Nigeria. There are about one hundred in South Africa. We have begun to network recently. Such networking meetings bring together music therapists and community music practitioners from countries of the continent. I am enthusiastic about what is emerging. There is a conversation ongoing about making training accessible and culturally sensitive. The work is cut for us. We know the place of music in the life of people in our continent. As such, we are sitting in the privileged position to harness musical, theatrical healing power, with an African flavour to the world.

Can we consider music therapy popular and widespread in Africa?

We need to go beyond the professional definition of music therapy to deeply appreciate the extent to which musical healing is prevalent in Africa. We can debate for hours about the impact of colonialism on the current definition of music therapy. However, it is hard to say that music therapy is a popular profession , considering that it does not exist in most countries on the continent.

Do you perceive considerable differences between your country and abroad (in the rest of Africa and across the world)?

I do not know what practical differences there may be in each of the countries of the world. I only sense that there could be conceptual and aesthetical differences if we consider music therapy and musical healing rituals. I have alluded to the possible distinctions in placing music therapy and simple music healing rituals. I believe we have a lot of work yet to be done in coming up with a synergical appreciation of music therapy that incorporates indigenous knowledge systems. Our work has involved the decolonisation agenda of research, clinical practice and theory. As a derivative of music healing rituals, music therapy has to be humble about its place in the human community. Those of us with academic credentials need to be modest about how we flaunt such qualifications and the privileges that go with them. Sometimes I wonder whether the repositioning of music therapy as a healing practice in the Western evidence-based medical model is colonial. Usurping knowledge and repackaging it to fit in the academy’s demands, has meant to relegate legitimate indigenous knowledge to some non-reliable expertise, and this can be problematic.

You are the WFMT regional liaison for Africa. Why did you choose to join the federation?

We live in times when the world is coming together more than ever before. I think you can recognise the global movement towards acting together. I believe that we can only find solutions to our significant problems in the world by working together. The World Federation of Music Therapy is a platform sharing the best ideas from the whole world. I like the idea of contributing with my voice to the development of music therapy in the globe.

Essential for me is to contribute and share with the world insights born out of the African sensibility and experience. As I have already said, we have debates to expand the definition of music therapy to include those elements ordinarily rejected due to lack of academic research rigour. I am interested in carrying out research informed by African perspectives. Given that we do not have many music therapists from continental Africa, I feel that the Sangoma/n’ganga musical healer wants to claim a place at the conversational table and make claims about the evidence of musical healing rituals inspired by the ritual users.

Among the WFMT’s purposes, we find the promotion of music therapy across the world as an art, as a science and as an educational way to support social justice and peaceful resolutions. What do you think and what can you tell us about it?

I hold the view that the WFMT has noble inspirations, particularly when we think about groups of people coming together to learn and growing in the great act of listening to one another. Learning is both an art and a science. When we think of science and the scientific approach that privileges experimentation, we can use such skills to enhance anecdotal learning. We can assemble knowledge through intuitive practices too. Art honours the intuitive and aesthetic intelligence of our being. Listening to each other is how we do justice. In a world where some voices have systematically and deliberately silenced, listening is a revolutionary act, mostly when we listen to voices that make us uncomfortable. Many voices in the world still want to be heard. If we use music as a metaphor, we need spaces where the previously silenced voice can sing opera. Music therapy is the context where we can dare to hear silent voices. Associations like WFMT are means through which we can speak to each other with courage.

Music has undoubtedly something to do with culture. Which kind of music do you play during therapy sessions? Is it typical and traditional African music? And which type of instrument do you use?

Music is indeed a culture carrier. However, in music therapy, we work tentatively with music. I cannot assume what music my patients prefer to use or work with. I am not particularly eager to make assumptions about the music that I bring in the therapeutic space. I work with music as it emerges within the therapeutic relationships, whichever way music is defined. I primarily use my voice in therapy. As a singer, I can manipulate my voice with relative ease. I can accompany the voice with instruments like hand drums, guitar, keyboards and other percussive instruments.

Can we consider music therapy as a way to get in contact with our cultural background and traditions? Do you think that this type of contact with cultural roots has psychological benefits?

If I wanted to explore issues concerning the patient’s identity and culture in my work, I would think such an approach would help. I want to emphasise that, in therapy, we work with the needs of the patient. It might intrigue me to explore cultural issues in treatment, but I cannot force a plan on the patient.

Do you think music therapy can be a way to practice a positive dialogue between different cultures and traditions?

I need to distinguish between music therapy – which is a particular way of working with a patient – and music therapy informed work. Within the clinical setting, music therapy has defined ways of working with the patient. Perhaps, if the question you might be asking is whether someone can apply music therapy skills in the cultural dialogue, I would say yes to that. We can apply music therapy skills to multiple situations such as cultural dialogue or community organisation. I have done work in the community by using the facilitation skills I would use in music therapy. I know music therapists who work in cultural dialogue spaces, and they employ music therapy skills. Of course, music therapy skills are transferable.

[Link to the Italian version]