Overcoming post-conflict trauma with art: three African case studies

When art is discussed in the public debate, it is often referred to as an activity reserved for wealthy collectors, radicals, or intellectuals. Most of the time, we do not see its value beyond mere aesthetics. Yet, art in its multiple forms is more than just entertainment. Its applications and benefits are many. For some people, it can help develop self-awareness. For others, it can become a medium through which to express distresses. Making art can become a therapy itself.

The use of art as an effective tool to improve mental health in individuals suffering from depression, schizophrenia, psychosis, bipolar disorder, or other similar pathologies has been proven by numerous scientific researches and supported by several international bodies such as the World Health Organization (WHO). Indeed, experiencing the arts helps raise the oxytocin levels – the so-called “love hormone” – in the hypothalamus.

This component is key to promote calm and boost regeneration during the healing process. It is also essential for the proper functioning of the mechanisms that enable the human recognition and control of complex emotions. Furthermore, engaging in creative exercises can mitigate feelings such as loneliness or sadness and improve the ability to build stronger social relationships, especially among individuals living in rural or disadvantaged areas.

Activities such as listening to music, dancing, and painting are all linked with the improvement of stress management skills in people affected by post-traumatic disorders. It was discovered that alexithymia (lack of emotional awareness) in patients with major depressive disorder can be reduced by involving the latter in creative activities such as working with clay. In addition, among adults and children who have undergone sexual abuse, terrorism, wars, and violence, studies show encouraging results regarding the value of the arts in communicating pain and regulating post-traumatic neurosis.

New-old methods to tackle mental illness and promote mindfulness in Africa

In numerous Sub-Saharan African countries, mental health issues are often more neglected than other medical conditions. In many parts of the continent, effective policies and initiatives aimed at developing psychiatric services and mental health care facilities are almost non-existent. Furthermore, misinformation, popular beliefs, and stigma play a big role in delaying the diagnose and treatment of these types of illnesses. As a result, people suffering from psychological and mental disorders often leave in fear, isolated from the rest of society.

All these factors combined, make it almost impossible to access appropriate drugs and qualified medical personnel. Hence, it is evident how there is still a long way to go before proper medical support is provided to individuals suffering from this category of disorders.

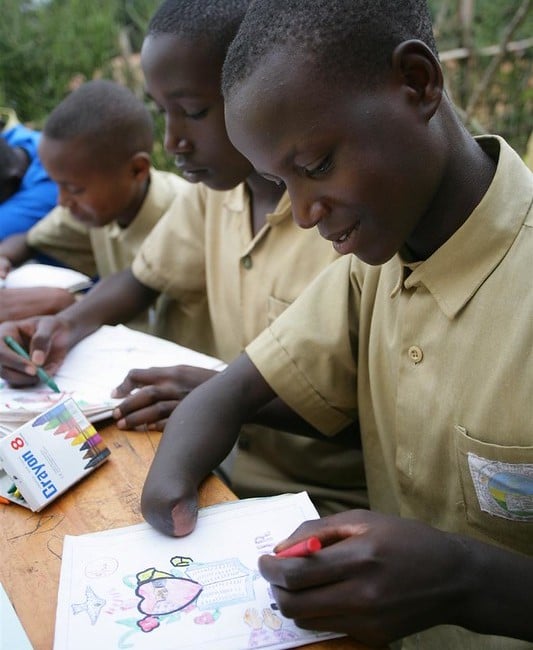

Could art represent a valid option to make up for this void? One of art’s many advantages is its accessibility. Anyone can grab a pen and paper, start drawing, and get lost in the process. Yet painting, sculpting, or dancing are all activities that can help release and channel complex emotions and repressed feelings, becoming allies in the treatment of mental disorders.

Moreover, art-based therapy can be effectively applied in extremely different social contexts. Similar practices to what the West labels “art therapy” can be traced in several parts of the world. In fact, the idea of attributing therapeutic abilities to art is by no means foreign to many African sociocultural environments. In particular, dance and visual arts are often fundamental parts of local traditions aimed at physical, mental, and spiritual healing.

Healing rituals involving dance play a remarkable role in the treatment of symptoms commonly associated with psychological distress. Among the best-known examples are: the ndeup rite in Senegal, the tsar ceremony – originated in Ethiopia and now widespread throughout North Africa, the voodoo in Benin (which heavily influenced the emergence of the santeria and other Afro-Caribbean and Afro-American traditions), and the abstract theatrical performances of Guinea.

As for the visual arts, it must be noted how employing artifacts as tools to promote or initiate physical or psychological recovery is common throughout the African continent. For instance, the Nigerian Yoruba healers use a variety of carved objects and statuettes during their sessions. In the same way, the naiba, used by the Kondo thaumaturges in the Democratic Republic of Congo, are vital to awakening the healing powers contained within the mikondi figures – needful parts of local medicine.

It is safe to say that a more creative and artistic approach to the treatment of trauma and mental pathologies can be effectively applied to accommodate different contexts and needs in Africa. All considered, it is more a matter of rediscovering and updating, rather than introducing from scratch, this particular take on dealing with psychological disorders.

Coping with gender violence trauma in North Kivu

Founded in 2010, the aim of the organisation Colors of Connection is to support vulnerable individuals to overcome traumas caused by abuses and post-conflict violence, championing affected communities through creative expression. The association operates in high-risk zones such as refugee camps in Mali and villages in Liberia that were heavily impacted by the civil war.

The project Courage Au Congo launched in Goma, capital of North Kivu, in 2016, is a great example of how art therapy can become a tool to manage and treat mental disorders in people who survived dramatic events.

In North Kivu, the state of violence and instability continues for decades. It intensified in 1996 due to the tug-of-war between numerous armed groups for the control of the region’s precious natural resources. The Democratic Republic of Congo has the largest coltan basin in the world which is an essential mineral for the production of tech devices and in all likelihood present in the item that you are now using to read this article.

One of the most disturbing aspects of this conflict is the use of rape as a weapon of war – this technique is perpetrated by rebel units to systematically intimidate, humiliate, dominate and terrorise the civilian population.

Human Rights Watch’s and the Norwegian Refugee Council’s statistics indicate that more than 6 million women, girls, and children have been brutally raped in eastern Congo since the beginning of the fight. The survivors experience devastating psychological damages such as phobias, post-traumatic stress disorders, depression, and anxiety, not to mention the social isolation provoked by stigma.

Goma is a population that is still traumatized with everything that has happened with war over and over again, rape, violence, the way that people have been killed – I think that the population is traumatized. But, art – it can heal. It gives joy, actually. When you see a drawing or a positive image, we become happy. I think this can be a way to detraumatize. (CAC member, Post-Project Evaluation)

The program run by Colors of Connection seeks to involve adult females and teenagers victims of abuses. The activities are specifically developed to stimulate the brain at a sensory and kinesthetics level in order to influence the self-regulation of emotions and promote mindfulness.

Through art-based reflective psychosocial therapy, carried out both in groups and individually, the participants have the opportunity to elaborate on their past, processing the pain in order to face and treat the mental illness that arose following gender violence they had to undergo.

The project impact report indicates how after the therapy participants showed a marked improvement in their ability to build interpersonal relationships and a decrease in anxiety and/or panic attacks.

Another interesting study carried on by the University of Sheffield in Sierra Leone emphasises the efficacy of art therapy to tackle PTSD. Like Congo, Sierra Leone, recounts a very high rate of violent rapes, over 62% of women are in fact victims of abuse. The project encouraged members of both sexes to take part in performances that consisted of a mixture of dance, theatre, and even stand-up comedy. It was highlighted how this can foster communication and advocate for women’s rights to mental health, inviting women to express their discomfort to men. Most of the time the first step toward healing is acknowledging that trauma actually exists.

Art-based therapy to improve mental health in post-genocide Rwanda

In 1994, Rwanda attracted international attention for the tragic events that occurred between April and June that year. The extent of the devastation brought in by the mass genocide was immense. In 100 days, more than 10% of the population (about 1.1 million people) was killed, and much of the country’s infrastructure was destroyed. More than 4 million people were displaced, half of them forced to flee to neighbouring countries.

Today the nation has relative political stability and registers consistent economic growth. However, most of its citizens are forced to live day by day with the psychological damages caused by war. The Government of Rwanda, supported by the United Nations and other regional bodies, has implemented various initiatives aimed at sensitising on and encourage the memory of the country’s tragic past, but there is an almost total absence of therapeutic support for people suffering from post-traumatic mental disorders caused by it.

In addition to the institutional fallacy, it should be taken into account that in the local tradition the open expression of emotions and the externalization of sentiments is not well received. The Rwandan culture does not encourage the open manifestation of feelings, especially the most intimate and painful ones. This makes it even harder for individuals affected by mental disorders to seek help and access treatment.

It was precisely this cultural predisposition to hold and contain emotions to inspire the work of the psychologist Valerie Chu. The expert worked for several years with the victims of violence in Kigali, using art therapy as a means to promote healing. Throughout the collaboration with local leaders and researchers, she developed an approach to art-based treatment that could be adapted to Rwandan cultural customs.

By studying local language, myths and proverbs, she noticed how traditionally there was a tendency to use containers such as pots, baskets, boxes, and vases as metaphors to describe the physical body whereases the feelings were interpreted as the content of these items. A well-known local proverb goes: “The suffering experienced by a cooking pot is understood only by those who scratch the bottom.”

Chu then began to encourage her patients affected by PTSD to create and decorate boxes with different colours or materials and then filling them with different objects. The psychotherapist reported how easily the idea of using a box as an avatar of the individual could be understood by Rwandans, and how this technique could help people to externalize and elaborate on their traumas in an indirect, but nonetheless effective way, unlocking the healing process.

Her work shows how the use of art therapy can be considered a valuable alternative for the cure of post-conflict psychiatric disorders in Rwanda, due to its unexplicit nature and the implication of symbols and allegories. Traumatic memories are often stored in the mind in the form of images and in this case, the creation and decoration of objects were proven effective in reducing the symptoms and helping victims overcoming their trauma.

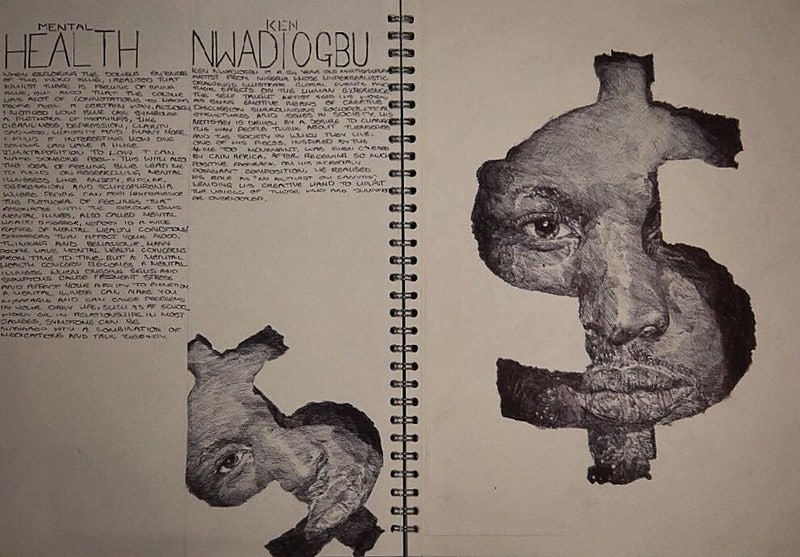

Art as a tool to address and understand psychopathologies

For vulnerable people fighting against trauma, depression, anxiety, and other types of mental disorders, art represents an opportunity to express their psychological narrative and hidden coping mechanisms. This brain dump can manifest itself through symbols, icons, colour codes, and so on. When backed by the assistance of a qualified professional who can proactively interpret the works, patients can begin to understand and deal with their mental distress.

It is not required to have any previous experience, artistic talent, or specific level of education to be involved in art therapy. This may be even more relevant in disadvantaged contexts where expressing certain feeling in a verbal or written manner can represent a challenge, and cultural barriers make harder to elaborate on traumatic memories in a more explicit way. This is why art therapy can be a valid, effective, and sustainable option. The goal is to appraise personal stories, reconnect the person to their emotions, and explore the past to fully live the present.

[Link to the Italian version]